Protectionist Trade Policies – The Wrong Move for America

Written as a policy analysis examining the economic theory and

providing quantitative analyses of the effects of protectionist trade policies

for those legislators who never took economics in college

Kyle Brewster

To the US House of Representatives Ways and Means Committee,

Pursuant to your request in search of the most economically

efficient means by which the government should use its power and influence for

the regulation of (or lack thereof) the United States’ economy, I have prepared

the following brief to provide useful information for such an endeavor.

Protectionism can be characterized by economic policies that

restrict imports from other countries by means of quotas, tariffs, and a

variety of other sorts of government regulation/intervention in an attempt to

protect domestic industries.

Scarce resources in the domestic markets are typically most

efficiently allocated by the free market. Therefore, the government should not

play a significant role in the interference with natural operations of the free

market unless the benefits of such interference result in a higher net benefit

to society than a lack thereof. The examples of government interventionist

policies that be will be examining in this brief include tariffs, quotas,

subsidies, and involvement in trade agreements.

Whenever it comes to discussion of proposed policy

initiatives, the number one priority of the government should be making

decisions with an in-depth analysis of cost versus benefits. Such a philosophy

for making decisions suggests that the best course of action for government

officials to take is one that provides the greatest utilitarian benefit while

reducing the costs or negative consequences of such decisions.

With this approach of analysis, decision-makers are able to

remain as objective as possible. Total benefits and the total cost are often

able to be measured quantitatively in both the short- and long-run. This is able

to render many of the political and emotional arguments that are frequently

made in attempts to gain favor for one side of the argument irrelevant and only

consider the objectivity of the data. As eloquently put by a professor of

political science during my university tenure, “Numbers don’t lie. People lie

about numbers.”

Summary: With

regards to protectionism being used as a tactic for promoting the welfare of

the economy and protecting domestic industries, here are my findings:

·

To suggest advocacy of protectionist principles

is taking steps back to the mercantilist economic conditions found throughout

16th-18th centuries, with the primary focus of increasing

exports, with less focus on the capitalization of comparative advantages and

less regards towards lowering price levels that domestic consumers face.

·

Tariffs are a means of restricting free trade, often

with the intention of protecting domestic industries. Tariffs tend to result in

a reduction of benefits to consumers that is greater than the increase of

benefits experienced by producers in a given industry. While there may be non-economic

benefits of tariffs, the cost to society at large tends to outweigh their

benefits. In addition, tariffs provoke retaliatory measures from the foreign

countries that are adversely affected.

·

Quotas have a similar net effect as tariffs.

Although the intended recipients of benefit may experience gains in production,

those gains are offset by a decrease in consumer benefit and a deadweight loss incurred

by society.

·

Even if countries enter into voluntary

agreements to restrict trade, there are still negative results.

·

Subsidies also result in a net overall loss to

society. While subsidies may benefit producers,

they come at a cost to consumers that outweighs benefits. In addition, subsidies

result in the overvaluation of the given good and is not a true representation

of the value deemed accurate by the free market.

·

Trade occurs when two parties engage in mutually

beneficial exchange. To inhibit such exchange is to inhibit the benefits

derived.

·

Rather than engaging in restrictive trade

policies to achieve domestic protection and achieve noneconomic objectives,

entering into trade agreements can be a more pragmatic means of achieving the

same goals.

Classical Schools of Economic Thought

The benefits of the specialization in production and the

benefits of trading can be found in economics schools of thought over 200 years

ago. Adam Smith, a Scottish philosopher and economist who lived from 1723 to

1790, is considered by many to be the “father of modern economics”

While the scale of the international economy did not exist

to the same extent during Smith’s lifespan compared to today, the principles he

found in his analyses continue to remain applicable. Smith referred to the

division of labor as the “greatest improvement in the productive powers of

labour, and the greater part of the skill, dexterity, and judgment with which

it is anywhere directed, or applied”

The effects of the division of labor can be observed on even

the most trifling of levels. This specialization of labor can be found in every

wealthy country – generally speaking, the farmer is nothing but a farmer, and a

manufacturer is nothing but a manufacturer

Regarding improvements in dexterity experiences, Smith

exemplified a blacksmith and a nailer (one who makes nails). A smith, who is

adept with hammer but whose sole business is not making nails, might only be

able to produce upwards of 200 nails in a given day (with a considerable rate

of rejects). Laborers who exercise no other trades but that of nail production

have been observed to be capable of making up to 2,000 nails in a given day.

Such discrepancies can be further increased with a given production-process is

broken down into multiple distinct operations

When a laborer begins work in a new trade, they are seldom

keen and hearty at the given process

Smith’s work additionally spoke to the advantage of

familiarity of a laborer with production machinery in their given trade.

Laborers are more likely to obtain easier/readier methods in pursuit of a goal

when their whole attention is directed at that single objective rather than a

great variety of things

Studies have been conducted that support the notion that

multitasking impedes on both physical and cognitive ability to complete tasks

The benefits of specialization of labor allow producers to

build a comparative advantage. A comparative advantage is defined as the

ability to perform a given task at a lower relative cost compared to

competitors

Ricardo argued that even if engaging in international trade

does not increase the value of a country, the mass availability of imported commodities

will benefit consumers by providing them with a higher purchasing power

resulting from lower price levels

Tariffs & Retaliatory Measures

Tariffs result in an overall net loss to society. While the

industry that such tariffs are attempting to protect may experience some

benefit, the negative effect on other industries and consumers tends to

outweigh those benefits. Refer to Appendix

A for further economic theory

analyzing the effects of tariffs.

For a contemporary example of the negative implications of

tariffs, consider the effects of the tariffs implemented by the Trump

administration in Section 232 that had the objective of protecting domestic

aluminum and steel production. As part of the platform of bringing jobs back to

America and putting “America First,” the Trump administration imposed tariffs

of 25 percent on steel imports and 10 percent on aluminum imports. These

decisions went against the consultation of Trump’s advisory staff

Trump took such measures to combat what he described as a

threat to national security created by imported metal that was a degradation to

the American industrial base, according to an investigation conducted by the

Department of Commerce

The actions by the Trump administration have also been

condemned in statements from the G7 meetings. The Finance Ministers and Central

Bank Governors asked the US Treasury Secretary to share their “unanimous

concern and disappointment” with regards to the tariffs

The purpose of these tariffs, according to the Trump

administration, was to adversely affect China and their flooding of US domestic

markets with cheap metals

As illustrated in Appendix

A, there is an inherent net loss to society at large that results from the

government’s issuance of tariffs. The reality of what happened to domestic

industries and price levels following the implementation of these tariffs

reflects what the economic theory suggests.

The Trade Partnership Worldwide - a consulting firm that

applies economic analysis to produce useful, clear, and concise information

about the impact of trade policies - conducted an analysis of the estimation of

the effects that these tariffs would have

The sectors of the domestic economy that would be positively

affected as a result of tariffs, quotas, and retaliatory measures include steel

producers, aluminum producers, and several other sectors that are able to

attract capital and labor from those displaced from sectors harmed by the

tariffs and resulting retaliation. The GDP of the United States as a result is

projected to decrease by 0.2 percent annually in the short-term along with a

decrease in projected exports

Employment in the steel and aluminum producing sectors is

projected to increase by 26,280 jobs, but reduce employment by 432,747 jobs throughout

the rest of the economy. The resulting total net loss is 400,445 jobs. In other

words, every one job gained in the aluminum and steel industries would come at

a cost of sixteen jobs lost in other sectors of the economy. The projected net

loss of jobs would be found in every state

Not only is there an inherent net loss resulting from using

tariffs as a tactic to protecting domestic industries, but, as previously

mentioned, retaliatory measures from the affected countries are almost

inevitable. Canada, the European Union, as well other affected countries say

that they have no choice but to respond with retaliatory sanctions of their own

Additional studies of the projected impacts of these tariffs

from other institutes expected similar economic woes. Dan Ciuriak and Jingliang

Xiao from the C.D. Howe Institute analyzed the reality of retaliatory measures

that would take place resulting from the steel/aluminum tariffs – a reality

that the Trump administration assumed would not occur. In their summary, they

found that the effects of the tariffs would result in the following: reduce US

imports by $23.4 billion; reduce US exports by $5.9 billion; reduce exports and

increase import penetration in user sectors, thereby worsening the US trade

balance (in the user sector) by $12.2 billion; reduce US shipments of user

products by $12.7 billion

† User sectors are defined by the Bureau of Industry and Security as the product that the purchaser of ultimately uses and is not re-exported (The Bureau of Industry and Security, 2018). These sectors in Ciuriak and Xiao’s study includes automotive, transportation equipment, machinery and equipment, and electronic equipment.

Their study and simulations further concluded that the

Section 232 tariffs would result in an artificially increased price level of US

goods. While higher price levels may yield some benefits for domestic

producers, it ultimately undermines the ability for the US sectors of steel and

aluminum-producing industries to remain competitive in the international market

as well as the competitiveness of user sectors

Apart from China and a few other countries, the US has

remained relatively friendly in terms of trade policies with our allies in

trade. The steel/aluminum tariffs, however, may be changing such a view from

other countries. Rather than remaining consistent with historical policies of

mutual benefit, the US appears to be flaunting its entrenched position of

trading power rather than making policy decisions that have the aim of positive

economic development and the promotion welfare (both for the US and its given

trading partner)

Ciuriak and Xiao analogized such demonstrations of power to

that of the Soviet Union prior to their fall. The implications of presenting

such a demeanor may unfold additional changes in our relationships with current

trading partners that could result in unfavorable consequences for the US in

the future

Furthermore, it is not possible to maximize the benefit of

the consumer when holding the interests of producers as a priority. Consider

the example of the “Negative Railroad” proposed by French economist Frederic

Bastiat in his first series of Economic

Sophisms in 1845

The idea of the negative railroad sprung from the

advancements in technology (e.g. locomotives) that allowed for transportation

to occur via land routes rather than being predominantly restricted to

waterways around the time of the Industrial Revolution. As a result of cheaper

transportation, producers were able to expand their market reach, thus breaking

up local monopolies (which are associated with higher prices and less power to

the consumer). With the railroad analogy, Bastiat made the connection of

tariffs and other protectionist measures having the same net effect as physically

destroying the rails and resulting in a reversion back to using more-costly

transportation methods

Measures that effectively restrict free trade and the resulting

subsequent negative unintended consequences are not unique to the current administration.

On June 27, 1973, the Nixon administration placed an embargo on the US

exportation of soybean products. The intended purpose of this embargo was to

combat high levels of exports and high prices that were the result of

government stock elimination

Prior to the 1973 embargo, Brazil’s soybean production

consisted of only about 18 percent of international sales, while the United

States help approximately 80 percent of worldwide sales

The United States’ decline market share in soybean

production can be connected back to the issue created with the Trump administration’s

tariffs on steel on aluminum. China is the world’s largest importer of

soybean-products, with demand topping 94 million metric tons

Quotas and Dumping

The negative implications of import quotas (a legal limit

imposed on the amount of a given good that may be imported) have a net loss to

society similar to that of a tariff. Refer to Appendix C for a further

explanation of the theory behind quotas.

Proponents of protectionist trade policies cite quotas as

being a beneficial means of preventing/combating import dumping. Dumping is

defined as the sale of goods in a foreign market below the price charged in the

given domestic market

Many economists, however, suggest an inherent infeasibility

with such a tactic. In the short-run, domestic firms may be at a disadvantage

as a result of foreign dumping. In the long-run, once the dumpers raise their

prices after establishing a dominant market share, the domestic competition is

likely to return. The dumping country would then have then only incurred a

long-term loss as a result from selling goods below costs. In addition,

domestic consumers benefit from the lower prices and can then use such price savings

to add to demand in other sectors of the domestic economy.

Consumer Benefit Derived from Free Trade

When producers are required to compete amongst each other

for the demand of consumers, price differentiation is commonly used tactic. Assuming

the quality of the goods from competing producers are the same, consumers will

be more attracted to the lowest prices. As a result, if producers want to

remain competitive with other producers in the industry, they will have to have

similar (if not lower) prices.

Consider the literature of Murray Rothbard, an American economist

and political theorist. Rothbard illustrated the benefits of trade with the

example of the trading relationship between the US and Japan – Japan being a significant

trading partner with the US that has the world’s third largest GDP valued at

approximately $5,070 billion

The effects of being trade allies with such a large economy

is found ubiquitously in American society with the products that consumers

purchase, especially electronics such as television sets, cars, microchips, and

etcetera. The reason consumers so readily purchase Japanese-produced goods over

American-produced goods is because Japanese prices are often lower and

therefore more competitive compared to American-produced prices

In the example of electronic product trade between Japan and

the United States, the transactions are mutually beneficial to each party.

Japanese producers are better off having a larger market to sell their product

and American consumers are better off by having an international purchasing

option with lower prices compared to domestic prices. Instituting any sort of

protectionist trade policies with the aim of benefiting domestic producers

would result in a deduction of American living standards who are rendered

unable to purchase high-quality and lower-priced electronics

Two countries engage in trade only if such a relationship is

mutually beneficial. Any sort of restrictions that inhibit the trading

relationship results in a reduction in benefits for both parties.

Voluntary Export Restraints

Even when two voluntarily agree to limit trade, there are still

negative implications to society at large similar to that of unilateral trade

restrictions. Consider the voluntary export restraints between Japan and the

United States with respect to the automotive industry in the late 1970s and

early 1980s. Due to competition from enhanced quality of imported cars, sales

of domestically produced cars in fell from 9 million in 1978 to an average of 6

million between 1980 and 1982

As a result of the declining profits from domestic

manufacturing, automakers and autoworker unions pushed for protection from

international competition. In May of 1981, Japanese car companies (one of the

primary sources of imports) agreed to restrictions of US sales of Japanese cars

to 1.68 million cars each year

Japan agreed to these conditions because it was their

least-costly option with regards to the US’s pursuit of protection for domestic

industries from foreign competition. The other option the US could have chosen

would have been tariffs on imports of Japanese cars, which would have cost

Japan an estimated $11 billion over the lifespan of the agreement

The limited supply of imported Japanese cars lead to an

increase of the prices of the imports by an average of about $1,200, around 14

percent higher than would have otherwise been without the restrictions

For many domestic manufacturers, this was an ideal situation

because they faced a considerable amount less of foreign competition. From 1986

to 1990, profits of domestic auto-manufacturers increased over 8 percent – this

increase amount to over $2 billion without adjustments for inflation

Not only did consumers face higher prices for Japanese cars

by a considerable margin, the decrease in competition enabled domestic

manufacturers to increase their prices. Because of the high price-demand elasticity

(defined as the responsiveness of quantity demanded to a change in price)

between quantity demanded and price of cars, domestic producers were only able

to raise their prices by approximately 1 percent, which equated to an average

of $400 unadjusted for inflation

The total net loss consumers in 1983 along was $4.3 billion

– the annual cost to the public was forecasted to (an in fact did) increase in

the following years

Even when adjusting the net effect to include gains to

domestic producers, the net loss to society was still upwards of $3 billion (or

$7.6 billion in 2018 dollars)

Robert Crandall, a senior fellow at the Brookings

Institution, estimated that the amount of jobs saved as a result of the import

restrictions was around 26,000

While we can observe the adverse effect on society at large (especially

consumers) in the automotive sector that were directly affected as a result of

the trade restrictions, the ultimate effect on the rest of society is difficult

to observe. It is safe to say, however, that the rest of society on average was

negatively affected.

When the United States restricts imports, our trading

partners as a result earn less revenue and can no longer can spend as much on

domestic exports. This decline in foreign demand results in a decline of

exports from domestic industries that export more-heavily. Less trade then

results in less demand for labor that services the international trade, such as

truck drivers for cross-country transportation and stevedores (those who unload

ships) for reception of shipments at ports

Protectionist Policies in the Form of Subsidization

Another tactic that is used in an attempt to protect

domestic industries from threats of global competition is in the form of

subsidization. Refer to Appendix D for an economic analysis of the net

effect of subsidies.

One example of government subsidization of domestically

produced goods is found throughout the agricultural industry. These policies

were initially implemented following the Great Depression where adverse

economic conditions and an unfavorable growing environment resulted in prices

farmers were able to sell their goods dropping by nearly two-thirds

To prevent a situation that could have resulted in the

agricultural industry’s inability to produce crops, the government became

involved with setting minimum prices - commonly referred to as price floors -

for crops produced and subsidizing farmers the difference between the natural

market price and the price

The result is an increase in the quantity supplied and a

decrease in the domestic demand. When only considering the domestic market, the

result of the price floor affects consumers in the form of either higher prices

or in the form of taxes paid for subsidization programs (see Appendix E). The opportunity cost of

those tax dollars otherwise going to other perhaps more economically efficient

government expenditure programs.

International demand for US agriculture products it at its

lowest point since 2010, with a trend of gradual decline since 2015

International Support for Free Trade

In more recent economic-history, The General Agreement on

Trade and Tariffs (GATT) was an organizational established to help promote the

mutually-beneficial principles of freer trade promoted by economists throughout

history. The GATT was a multilateral agreement signed in 1947 with the purpose

of the “substantial reduction of tariffs and other trade barriers and the

elimination of preferences, on a reciprocal and mutually advantageous basis"

On January 1, 1995 the World Trade Organization (WTO)

replaced the GATT. Following the WTO’s birth/transformation, it now serves as a

permanent organization with an increased scope of coverage, helping to

establish international economic regulations and settle disputes between member

countries. There are 164 member currently part of the WTO and adhere to the

organizations principles and legal requirements

Trade Agreements

The enabling of competition on the international level has

effectively raised the standards of living of consumers from all countries

involved by providing consumers with access to lower prices. One route that the

federal government can take to obtain such benefits is by taking entering trade

agreements

One type of foreign trade policy that pursues the goal of

more open trade is with regional trade agreements. The WTO defines regional

trade as agreements as reciprocal trade agreements between two or more partners

– they include free trade agreements and customs unions

Another type of trade agreement are preferential trade

agreements. These are defined by the Congressional Budget Office as treaties

between two or more countries that remove barriers to trade and establish rules

and regulations for international commerce between the involved parties

One economic benefit of more open trade (that can result from

trade agreements) in an increase in workers’ productivity in the long-term.

Reconsider the previous example of the US-Japanese electronics industry

In the long-run, those workers who are displaced from the

relatively inefficient sectors are able to transfer their labor to sectors in

which the US holds a comparative advantage and are thus able to be more

productive. Higher productivity results in higher industry average real wages

and output, benefiting both producers and consumers

In addition to the reallocation of labor/resources into more

productive industries resulting from more global competition, it also forces

firms to make physical capital, production process, and other innovative

investments in an effort to remain globally competitive

This can result in competition amongst producers in the form

of higher wages as an incentive to attract more productive workers. Not only do

these higher-paid workers then have a higher income (and thus are able to add

to demand in other consumption sector of the economy), but their additional

productivity contributes to lower prices for the products produced of the firm by

which they are employed.

Lower prices as a result from the importation of foreign

goods has a greater beneficial impact on lower-income consumers compared to consumers

of other demographics – especially in the sectors of food and clothing

There are also non-direct economic reasons that a country might

be incentivized to enter into a trade agreement. Conditions of an agreement

between two countries could include terms that address protection of

intellectual property rights, phytosanitary/sanitary standards (plant/animal), data

transfer/localization rules, and requirements of certain environmental and/or

labor standards just to list a few

With regards to protectionist policies, trade agreements work

towards the mitigation of tariff and quota rates. Prior to the first Geneva round (which

established the GATT), tariffs rates of major involved countries was 22 percent

Policy Alternatives

One course of action that we could take is to continue with

how the Trump administration is currently attempting to address certain

domestic and political issues with the use of tariffs/other protectionist

policies. While they do result in net losses to society, there are some

benefits that they can bring.

The domestic industries that the tariffs are intending to

protect are in fact working. Domestic steel and aluminum manufactures have

experienced real gains since the issuance of the tariffs that provided benefits

to workers and producers in those industries; however, as we have discussed,

the benefits that they provide to the steel/aluminum industries are

significantly outweighed by the cost to society (in addition to the deadweight

loss paid by society and the inevitable retaliatory measures).

Another argument that is commonly made is with respect to

worker wages. This argument, however, often fails to consider the productivity

of those workers. Productivity and employee wages tend to be positively

correlated.

For example, if an American worker is paid $20 per hour. With

a higher wage incentive and the capital (machinery or other technology) at

their disposal, they can produce 100 units of a given good per hour. In a

foreign economy, a worker may be paid $2 an hours and produce only $5 units per

hour doing their work solely by hand

If the previous example is the case, the discrepancy between

the resulting productivity yielded from wages paid is negligible. If foreign

sub-par treatment of equally productive workers on the other hand is the case,

then domestic producers are in fact at a disadvantage and that must be

acknowledged. Regardless of the potential for such a disadvantage, I believe

there are better ways to deal with those issues (I will elaborate on that in my

policy recommendation section).

As previously mentioned, proponents of protectionist trade

policies may cite tariffs, quotas, or subsidies as a means of preventing and

combating dumping. Even after considering the long-run economic infeasibility

of such a market-penetration strategy, the WTO has the authority to present

legal ramifications against its member countries who attempt to employ such a

strategy.

According to Article VI of the GATT (which is still in

effect as part of the WTO), all member countries are subject to the antidumping

provisions set forth by the WTO (World Trade Organization, 2018).

Rather than incurring the deadweight loss to society as a

result of protectionist policies to combat dumping (the cost of which if often

paid by consumers), the US should let the legal authority of the WTO deal with

foreign economies guilty of such strategies. For countries that are not members

of the WTO, then and only then might protectionist trade policies be the most

beneficial route to take for the welfare of the domestic economy.

Another route we could take is one of eliminating all

tariffs, quotas, and other forms of trade restrictions/protectionist policies

in all forms. Theoretically speaking, the benefits of allowing free trade speak

for themselves; however, there would be numerous implications to such a

strategy.

For one, we must consider the reasons we having some of our

current trade restrictions. If countries that are not subject to the

jurisdiction of the WTO are engaging in unfair trading practices, then pursing

this route regarding protectionist trade policies would leave the US unable to

combat such unfair practices.

In addition, such a radical change would most likely not be

viewed very favorably in the eyes of the public (especially for domestic

producers who may be put at a significant comparative disadvantage).

Policy Recommendation

An alternative route that I believe would be our best option

would be an approach that is more mutually-beneficial. That approach would

consist of the elimination (if not, a significant reduction) in the amount of

protectionist trade polices federally legislated. In further pursuit of the

benefits obtained by free trade, we ought to engage more in free trade

agreements with other countries (especially with historically adversarial

trading partners).

Consider the dynamics of the US’s trade relationship with

China (the United States’ biggest trading partners, especially in terms of

imports). I suggest we enter negotiation with the goal of a bilateral preferential

trade agreement.

I believe that this route could change the dynamic of economic

relationship between the US and China. This way, we could set terms and

conditions regarding how we can maintain a trading relationship that brings

benefits to both parties, rather than the current dynamic of attempts at benefiting

each respective domestic economy at the cost of the other. In terms of game

theory, we ought to purse a tit-for-tat strategy using compromise/cooperation

rather than retaliation compared to the mentality of a zero-sum game (our

benefits coming at China’s loss).

As mentioned previously, foreign wages (as a result from

insufficient foreign labor laws) may be putting domestic firms at a

disadvantage. Rather than a series of subsidies or retaliatory tariffs/quotes,

negotiations through the process of trade agreements can help to address the

issue.

Consider the recent renegotiation of North American Free

Trade Agreement (NAFTA) regarding automotive manufacturing wages with respect

to Mexico. Under the renegotiation of NAFTA (now the US-Mexico-Canada

Agreements, or USMCA), 40-45 percent of automotive content must be made by

workers earning at least $16 USD per hour

I believe we could use a similar tactic to achieve both

political objectives and eliminate unfair competition with other countries by

pursing this route.

While this option may the most pragmatic approach to take, a

significant issue with pursing such a route is with public support. Some of the

population will view an anti-protectionist approach to trade policy as

“un-patriotic” considering it might result in the displacement of jobs in

domestic industries, such as those in manufacturing or agriculture as

previously discussed. This is when the role of government suasion comes to be a

necessity

In order to gain public approval, the government has the

responsibility of using relevant data at its disposal to demonstrate that an

anti-protectionist approach is best way improve societal benefit with the least

cost. A cost-benefit analysis of the effects of removing protectionist trade

policies can be published that show a forecasted impact of policy decisions

Such an analysis can be done by constructing statistical models

based off of historical numbers (adjusted for inflation) that represent the

effect on employment and consumer benefit gained following the elimination of

protectionist trade policies. These models could then be used to forecast the

results that my suggested approach would have on the current economy.

Even with the best models and attempts at forecasting, it is

still impossible to predict the future with 100 percent accuracy. An

incremental approach would be the best way to minimize the short-term effects.

With this tactic, we would be better able to monitor deviations from model

predictions between actual results and adjust policy measures accordingly prior

to the implementation the next stage of protectionist-reduction. The stages of

implementation of reduction in protectionist policies would be a gradual

decrease in rates of tariffs/quotas/subsidies/etcetera rather than an immediate

elimination).

Even after illustrating the benefits that consumers would

experience, there are still issues presented with those whose jobs are

displaced as a result of these policy changes. Some of those displaced will be

low-skilled blue-collared workers that do not have skills that are easily

transferable to other industries (or who have high-skills that are still not readily

transferable).

The government can alleviate this burden by using some of

the benefits gained by consumers (resulting from lower prices) to provide

short-term assistance to those displaced (short-term assistance because

structural changes of the economy over the long-run will negate the negative short-term

impact).

The collection of programs underneath the Trade Adjustment

Assistance (TAA) for Workers Program part of the Department of Labor could be

used to help with such a process. The purpose of the TAA is to provide

assistance to workers who have been adversely affected by foreign trade

Not only would this provide direct benefits to the displaced

workers, but it would also minimize those becoming reliant on the welfare

system. Proper usage of the TAA program could provide the displaced workers with

transferable skills, who could then add to productivity in other sectors of the

domestic economy in additional to no longer needing government benefits.

Regardless of the specificities of the program, government

intervention to address the needs of those workers is a necessity as stated by

the Founding Fathers regarding the role of the government – to “promote the

general welfare [of the people]”. This approach that I suggest would

immediately benefit consumers and over the long-run and set the trend of

increased productivity in domestic production for generations to come.

Appendix A – Economic Analysis of Tariffs

The term consumer

surplus is defined as the difference between the prices that a consumer/buyer

is willing to pay for a service or good compared to the price that they

actually pay. It is calculated by subtracting the price paid from the maximum

buying price. When being derived graphically, it is the area below the demand

curve and above the effective price.

Similarly, the term producers’

(or sellers’) surplus is defined as the difference between the prices that a

seller/producer receives for a good compared to the lowest or minimum price

that they would have been willing to sell the good. It is calculated by

subtracting the minimum selling price from the price received. When being

derived graphically, it is the area above the supply curve and below the

effective price

A deadweight loss is

a term used to refer to the loss to society of not producing at the naturally

competitive level of output. When the market is at a state of perfect competition, the given market

meets four basic assumptions: there are many sellers and buyers, the sellers

sell a homogenous good, buyers and sellers have all relevant information, and

entry into and exit from the market is relatively easy. In such a scenario, the

price is determined by the market and producers must respond accordingly

|

(Arnold, 2016)

While the reality of the free-market is seldom (if ever) at a state of perfect

competition, it helps with the comprehension of the economic models that can be

useful when applied to real-world situations. With an understanding of the

elementary economic terms, we are able to observe the effects of government

interventionist policies on the natural state of the supply and demand of the

otherwise free-market. Consider the following graph:

Prior to the effects of the tariff, the consumer equilibrium

consisted of the area marked by 1-6 and the consumer surplus is the areas

marked by 7. Because there is no interference in the market at this point,

there is no revenue collected by the government.

Following the implementation of the tariff, there are

changes in the consumer surplus, produce surplus, and amount of revenue

collected by the government. The consumer surplus decreases by the areas market

3-6, leaving the surplus to be the areas marked by 1 and 2. The produced

surplus increase by the area marked 3, thus increasing the consumer surplus to

3 and 7. The amount of revenue generated by the tariff collected by the

government is market by the areas 5 (which can also be calculated by multiplying

the amount of the tariff by the market quantity).

After considering the effect on the producer surplus, the

consumer surplus, and the amount collected by the government, there still

remains the areas marked by 4 and 6. These two areas represent the deadweight

loss to society – the value that is not gained by producers, consumers, nor in

the form of revenue collected by the government, thus resulting in a net loss

to society as a whole.

Appendix B – Game Theory

Game theory is

defined as “a mathematical technique used to analyze the behavior of decision

makers who try to reach an optimal position for themselves through game playing

or the use of strategic behavior who are fully aware of the interactive nature

of the process at hand, and who anticipate the moves of other decision makers”

in a competitive environment

There are different types of “games” that can be applied to

real-world situations. A zero sum game

is a scenario when the benefit achieved by one participating party comes at the

expense of the other party. Zero sum games are exemplified in the world of

business when two businesses are competing for a customer. There can only be

one party involved to win the business of the customer.

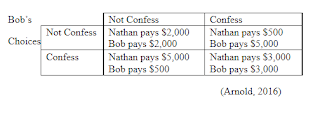

Consider a game-theoretical analysis in the example of the ‘prisoner’s dilemma’. In this example, each party knows the options of the other party and are unable to communicate with the other to formulate any sort of strategy. The outcome as a result of each combination of actions is listed as follows:

In this situation, regardless of whether or not Bob

confesses, Nathan will be better off by confessing. Similarly for Bob,

regardless of whether or not Nathan confesses, Bob will be better off by

confessing. As a result, both parties will end up confessing and end up in box

4, with each paying a $3,000 fine; however, if they would have been able to cooperate, they could have both chosen not

to confess and each only face a $2,000 fine.

A tit-for-tat game

theory strategy is a game theory strategy that realizes the benefit of

cooperation in competitive games and utilizes such a benefit until otherwise

provoked (such as the negotiation of trade deals). This strategy was discovered

by Robert Axelrod as an application for the prisoner’s dilemma example except

lasting multiple rounds. The mathematically-optimal scenario throughout

multiple tests was to begin by not confess and continue to not confess until

the opponent confessed. Once the opponent confessed, the program would then

“punish” the opponent by confessing

For a more applicable example, consider two national economies. Economy A may attempt to utilize the benefits of free trade by not imposing tariffs on economy B as a gesture of preliminary cooperation. If economy B chooses not to impose tariffs and allow free trade with economy A, then the two economies would continue with cooperation and both benefiting; however, in economy B chooses to implement tariffs, then economy A would subsequently retaliate with tariffs.

Appendix C – Economic Analysis of Quotas

(Arnold, 2016)

Consider an import quota on a given good imposed by the US government. Prior to the implementation of the quota, domestic demand matches the price world price at its state of equilibrium. If domestic production does not meet domestic demand, then the difference in demand is imported into the US (the difference is that area marked Q2 – Q1). As a result, the consumer surplus is market by the areas 1 – 6 and the producers’ surplus is the area marked 7. Foreign suppliers are benefiting by the areas marked 4 – 6.

Following the implementation of the quota, the domestic

price is increased (as a result of the decrease of supply of the good) to the

point marked PQ. The consumer surplus is decreased to the areas

marked 1 and 2 (because they can no longer enjoy the relatively cheaper

imported good). Producers surplus increases to the areas now marked 3 and 7

(because of less competition from imports, demand for domestically produced

goods will increase despite higher price levels). The benefits that foreign

producers receive from exporting their good to the US decrease to the area

market 5.

Similar to the net effect from a tariff, the areas marked by

4 and 6 are not gained by producers, consumers, or from foreign producers, and

is thus a deadweight loss/net loss to society.

Appendix D – Economic Analysis of Subsidies

For simplicity of analysis, we will consider the scenario of

a government-issued subsidy per unit produced provided to consumers. Consider

the following graph:

(Landsburg, 2008)

Prior to the subsidy, the economy remains at a state of

equilibrium where supply is equal to demand. This results in a consumer surplus

of A and C and a sellers’ surplus of F and H. Consequently, the total net

benefit to society at such a market-state is represented by the areas A, C, F,

and H.

A per unit subsidy on consumers results in the demand curve effectively

shifting to the right (because at any given quantity, consumers are willing to demand

a higher quantity of the given good because of the incentive of the subsidy).

As a result, the consumer surplus consists of the area marked by A, C, F, and G. The suppliers’ surplus now consists of the area marked by C, D, F, and H. The cost of the subsidy to taxpayers (which can,

similarly to the cost of a tariff, be calculated by multiplying the quantity

times the quantity of the good consumers/produced) is composed of the area marked by C, D, E, F, and G.

After considering the additional consumer and supplier

surplus, the total benefit to society consists of the areas marked A, C, F, and

H. After considering the cost of the subsidy to taxpayers, the difference is the

cost paid by taxpayers in the area market E. In this case, E represents a

deadweight loss to society.

Appendix E

When a price floor is implemented, the government sets the market price for a given good above that of the otherwise equilibrium price of the natural market. Consider the following graph:

(Arnold, 2016)

Government-set maximum pricing, also referred to as price

ceilings, has a similar net effect on society (such as rent control in the

real estate market).

Works Cited

Arnold, R. A. (2016). Microeconomics (12 ed.).

Boston, MA, USA: Cengage Learning.

Aune, J. A. (2002). Selling the Free Market: The

Rhetoric of Economic Correctness. Part I - Rhetoric, Economics, and

Problems of Method. New York, USA: Guilford Publications. Retrieved

November 9, 2018, from https://www.guilford.com/excerpts/aune.pdf?t

Bastiat, C. F. (2011, May 18). A Negative Railway.

Retrieved November 9, 2018, from Mises Institute:

https://mises.org/library/negative-railway

Benjamin, D. (1999, September 1). Voluntary Export

Restraints on Automobiles. 17(3). Retrieved from

https://www.perc.org/1999/09/01/voluntary-export-restraints-on-automobiles/

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2018). CPI Inflation

Calculator. Retrieved November 11, 2018, from BLS - Databases, Tables

& Calculators by Subject:

https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm

Chad P. Brown, D. A. (2015, December). The GATT's

Starting Point: Tariff Levels Circa 1947. NBER Working Paper Series.

Retrieved November 12, 2018, from

https://www.dartmouth.edu/~dirwin/docs/w21782.pdf

CLAL. (2017, July 27). Corn and Soybean Outlook.

Retrieved November 11, 2018, from

https://news.clal.it/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/MAIS-SOIA-LUG-17-EN.pdf

CLAL. (2018, October 19). Corn and Soybean: World

Market Trends. Corn and Soybean. Retrieved November 11, 2018, from https://news.clal.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/CLAL-Slideshow-Corn-and-Soybean-OCT18.pdf

CoinNews. (2018). US Inflation Calculator. Retrieved

November 11, 2018, from https://www.usinflationcalculator.com/

Congressional Budget Office. (2018, September). How

Preferential Trade Agreements Affect the US Economy. Retrieved November 9,

2018

Crandall, R. W. (1987). The Effects of U.S. Trade

Protection for Autos and Steel. Brookings Paper on Economic Activity, 1987(1),

271-288. doi:10.2307/2534518

Dan Ciuriak, J. X. (2018, June 12). Working Paper -

Trade and International Policy. Quantifying the Impacts of the US Section

232 Steel and Aluminum Tariffs, 1-13. CD Howe Institute. Retrieved

November 8, 2018, from

https://poseidon01.ssrn.com/delivery.php?ID=1450650171191190261061180230710100270080780020740400501250800740310260311110640120990430270420320270320540691220310010000181270400870590200450900870980000740040820760190730800640700810191151141161240681201160251

Dr. Joseph Francois, L. M. (2018, June 5). Policy

Brief - Round 3: 'Trade Discussion' or 'Trade War'? The Estimated Impacts

of Tariffs on Steel and Aluminum, 1-8. Washington D.C, USA. Retrieved

November 8, 2018, from

https://tradepartnership.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/232RetaliationPolicyBriefJune5.pdf

Drezner, D. W. (2018, June). The Economic Case for

Free Trade is Stronger than Ever. Retrieved from Reason:

https://reason.com/archives/2018/04/30/the-economic-case-for-free-tra

Duke Law. (2017, October). GATT/WTO. Retrieved

November 11, 2018, from Duke Law - Research Guides:

https://law.duke.edu/lib/researchguides/gatt/

Employment and Training Administration United States

Department Of Labor. (2017). Trade Adjustment Assistance For Workers

Program. US Department of Labor. Retrieved November 12, 2018, from

https://www.doleta.gov/tradeact/docs/AnnualReport17.pdf

Helene Hembrooke, G. G. (2003, September). The laptop

and the lecture: The effects of multitasking in learning environments. Journal

of Computing in Higher Education, 15(1), 46-64. Retrieved November 11,

2018, from https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02940852

International Monetary Fund. (2018). GDP, Current

Prices (Billions of Dollars). Retrieved November 9, 2018, from IMF

DataMapper: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPD@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD?year=2018

Landsburg, S. E. (2008). Price Theory and

Applications. Mason, Ohio, USA: Thomson Higher Edcatino.

Office of the United States Trade Representative.

(2018, October). United States–Mexico–Canada Trade Fact Sheet - Modernizing

NAFTA into a 21st Century Trade Agreement. Retrieved November 11, 2018,

from

https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/fact-sheets/2018/october/united-states%E2%80%93mexico%E2%80%93canada-trade-fa-1

Peters, B. G. (2013). American Public Policy -

Promise and Performance (9 ed.). Los Angeles, California, USA: SAGE

Publications.

Rachel F. Adler, R. B.-F. (2012, Feburary). Juggling

on a high wire: Multitasking effects on performance. International Journal

of Human-Computer Studies, 70(2). Retrieved November 11, 2018, from

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2011.10.003

Ray, D. E. (2018). Nothing intensifies food

security concerns like food unavailability. Knoxville, Tennessee:

Agricultural Policy Analysis Center - University of Tennessee. Retrieved

November 11, 2018, from https://www.agpolicy.org/weekcol/217.html

Ricardo, D. (1817). The Works and Correspondence

of David Ricardo, Vol. 1 Principles of Political Economy and Taxation

(Vol. 1). (M. H. Piero Sraffa, Ed.) Retrieved from

http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/ricardo-the-works-and-correspondence-of-david-ricardo-vol-1-principles-of-political-economy-and-taxation

Roger LeRoy Miller, D. K. (1992). The Economics of

Macro Issues (7 ed.). St. Paul, Minnesota, USA: West Publishing Company.

Rothbard, M. N. (1995). Smashing Protectionist

"Theory" (Again). Retrieved November 9, 2018, from The Mises

Institute: https://mises.org/library/smashing-protectionist-theory-again

Smith, A. (1789). The Wealth of Nations (5

ed.). (L. S. Economics, Ed.) England.

Smith, A. (2008). The Invisible Hand. New

York, New York, USA: Penguin Books.

Statistica. (2018). Import volume of soybeans

worldwide in 2017/18, by country (in million metric tons). Retrieved

November 11, 2018, from Statitica Portal: https://www.statista.com/statistics/612422/soybeans-import-volume-worldwide-by-country

Swanson, A. (2018, March 1). Trump to Impose

Sweeping Steel and Aluminum Tariffs. Retrieved November 8, 2018, from The

New York Times: https://www.polyu.edu.hk/cnerc-steel/images/news_events/news/news20180301nyt.pdf

The New York Times. (1973, July 7). Japanese Upset

by U.S. Soybean Curb. Retrieved from New York Times Archives:

https://www.nytimes.com/1973/07/07/archives/japanese-upset-by-us-soybean-curbs-u-s-ban-on-soybean-exports-is.html

The World Trade Organization. (n.d.). Regional

trade agreements and preferential trade arrangements. Retrieved November

9, 2018, from World Trade Organization:

https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/region_e/rta_pta_e.htm

Thomas R Swartz, F. J. (2004). Taking Sides -

Clasing Views on Controversial Economic Issues (11 ed.). Guilford,

Connecticut, USA: The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.

Trade Partnership Worldwide, L. (2018). About Us.

Retrieved November 8, 2018, from The Trade Partnership: https://tradepartnership.com/about-us/introduction/

UNM - Library. (1995). 4.2 Government Intervention

in Market Prices: Price Floors and Price Ceilings. Retrieved November 12,

2018, from UNM - Library:

https://open.lib.umn.edu/principleseconomics/chapter/4-2-government-intervention-in-market-prices-price-floors-and-price-ceilings/

US Department of Agriculture. (2018, November).

Oilseeds: World Markets and Trade. China Soybean Imports Lowered: Imports

Down 16 Million Tons since June. USDA. Retrieved November 11, 2018, from

https://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/circulars/oilseeds.pdf

USDA. (2017, May 7). Agricultural Trade.

Retrieved November 12, 2018, from United States Department of Agriculture -

Economic Research Service: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/ag-and-food-statistics-charting-the-essentials/agricultural-trade/

World Trade Organization. (2016, July 29). Members

and Observers. Retrieved November 11, 2018, from World Trade Organization:

https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/org6_e.htm

World Trade Organization. (2018, June). WTO

ANALYTICAL INDEX. Anti-Dumping Agreement – Article 6 (Jurisprudence).

Retrieved November 12, 2018, from https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/publications_e/ai17_e/anti_dumping_art6_jur.pdf